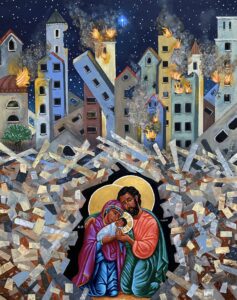

Christ in the Rubble icon (c) Kelly Latimore https://kellylatimoreicons.com/en-gb

THIS CHRISTMAS, in Palestine and Israel, in Sudan, in Ukraine and in other less publicised parts of the globe, darkness and violence seem overwhelming.

In Bethlehem, traditionally the birthplace of Christ, seasonal celebrations have been cancelled in respect for the unfathomable suffering of nearby Gaza – where 1.9 million have been displaced, 24,000 (including nearly 11,000 children) killed, many more thousands injured, and the population faces starvation [UN Special Rapporteur estimates].

“The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light; those who dwelt in a land of deep darkness, on them has light shone”, declared the Hebrew prophet, Isaiah. Right now, that light feels as if it has almost been extinguished. Almost, but not quite. A candle does not flicker in a room that is already accessible to illumination.

At the recent Liturgy of Lament in Bethlehem, where the infant Jesus was laid in the rubble of war and destruction, the note of hope was certainly not lost – but the demand on Christians and on all people of goodwill to raise their voices unequivocally against indiscriminate bombing, summary executions, ethnic cleansing and, yes, genocide, was at the heart of the powerful address given by Evangelical Lutheran pastor, the Rev Dr Munther Isaac.

His message, effectively spoken on behalf of all the historic Christian communities in the region, was unflinching: “If you are not appalled by what is happening in Gaza… there is something wrong with your humanity… We, the Palestinian people, will recover… but for those who are complicit, I feel sorry for you. Will you ever recover from this?”

Other Christian leaders, from the Latin Patriarchs to the Pope, have added their voices. So has US Quaker director for Middle East policy, Hassan El-Tayyab. “While Christians around the world are celebrating the Prince of Peace, Jesus Christ, Palestinian families in Gaza will be struggling to find food, shelter, and medicine, and trying to dig their loved ones out of the rubble.”

The murder of 800 Israeli civilians and 400 largely unarmed soldiers by Hamas militants on 7 October was horrific, criminal, inhumane and inexcusable. It was an act of utter barbarity which has no place in legitimate resistance to a long and terrible history of occupation and apartheid suffered by the Palestinian people over many decades. Some of those murdered or kidnapped were themselves Israeli peace activists. Both Hamas and the Netanyahu-marshalled far right in Israel share ideologies of mutual annihilation.

But what has followed for over two and a half months at the hands of the IDF in Gaza, and the 270 killings carried out by settlers in the illegally occupied West Bank, is not self-defence, either. It is slaughter, forced displacement and collective punishment on a massive scale, with the direct complicity of the United States, the United Kingdom and others in our deeply fractured ‘international community’. Hospitals, schools, shops, homes and infrastructure have been wiped out, as well as many thousands of lives. Hundreds of UN staff, humanitarian workers and journalists have also been killed. These are war crimes which have been justified and even celebrated with religious and scriptural rhetoric as well as political, ideological and military posturing.

In the midst of such inhumanity comes the message of repair, peace, restoration, justice and salvation (being healed and made whole again) in the birth of a small infant on the edge of empire in squalor, uncertainty and obscurity. The infancy narratives in the gospels wrap this story of hope-from-the-margins and the coming of God in darkness and vulnerable flesh within a series of disruptions to human ‘business as usual’ for both rulers and ruled. This is reflected in different but surprisingly complementary ways by the radical monk, mystic and activist Thomas Merton and the somewhat conservative modernist poet, critic and dramatist T. S. Eliot.

For Merton, the disruption is the disjuncture between two ways of seeing the world: the competing realities of wholeness and brokenness, justice and tyranny, peace and war, beauty and terror, God’s commonwealth and our imperium. In one of these realities – the one Advent asks us to bear in hope without the visible presence of deliverance – Christ is inscrutable, unnoticed and (frankly) unwanted. “Into this world, this demented inn, in which there is absolutely no room for him at all, Christ comes uninvited.” His message of costly peace is not ‘realistic’ in a world of war made in our corrupted imaginations.

But because he cannot be at home in it, because he is out of place in it, and yet he must be in it, his place is with those others for whom there is no room. His place is with those who do not belong, who are rejected by power because they are regarded as weak, those who are discredited, who are denied the status of persons, tortured, exterminated. With those for whom there is no room, Christ is present in this world. He is mysteriously present in those for whom there seems to be nothing but the world at its worst. (Thomas Merton, ‘The Time of the End Is the Time of No Room’, in Raids on the Unspeakable, New Directions, 1966, pp. 51-52.)

In his ageless poem ‘Journey of the Magi’ (first published as a pamphlet in the Ariel Poems series in 1927), Eliot further suggests that the privileged magi could barely have comprehended the upending profundities of the unfolding mystery they were to witness in its lowly initial manifestation. Indeed, hollowed-out humanity (“lost violent souls”) may appear to have seen the light but is unable either to recognise its source or to follow it, and so faces withering and death in the wilderness. To receive the birth of the Christ-child in its full transformative significance, much of what appears ‘normal’ in a world of spiritual and moral emptiness will itself need to die, including the kingdoms of this age, against which the gentle realm of God is set. As the speaker in the poem confesses:

All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly,

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

The business of peace on earth was given to ordinary people like us through the Christ-child in the stable. But what was also given was the opportunity to recognise that what diminishes humanity is within us as well as outwith us; in our hearts as well as in our politics. Among other places, it is in the inner violence we do to ourselves by accommodating the outer violence, injustice, abuse, torture and oppression which our systems of power perpetuate, as Dr Isaac pointed out in his recent Bethlehem sermon.

I will give the penultimate word to Conrad L. Kanagy, who has recently gifted us a wonderful biography of doyen biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann (to whom we might fruitfully turn when texts of warning and terror are weaponised in support of the contemporary slaughter of innocents aimed at “those for whom there is no room”.)

If the Christmas story has any truth at all, then it is an epic tale of peace and hope and light for the entire world across all time and space. Its promise is not only for a lucky few in the right place at the right time and believing all the right things.

Writer Jeanette Winterson, herself a survivor of restrictive and exclusive faith, sums it all up wonderfully in the Christmas 2023 edition of the New Statesman magazine:

You don’t need to be a believer to meditate on the power of this story. It’s not a hero saga. It’s a story about hundreds, then thousands, then millions of people letting go of their old gods and beliefs, and remaking their minds. Now, I know that religion has a lot to answer for. No excuses. Humans can’t manage to live in the light for long, it seems. That doesn’t mean the light is not there, or that we are not drawn to it. Changing the way we live is the only way to sustain life on Earth. The old dogmas, the false gods we worship – economic growth, wealth, power – must be put aside. The beauty and mystery of the Nativity story is found in the symbol it offers of new life, unprotected and vulnerable. Impossible. But only the impossible is worth the effort.

[The ‘Christ in the Rubble’ icon painting is being promoted by Red Letter Christians and others to raise money for humanitarian relief in Gaza. Details here. Please also visit Kelly Latimore.]

———–

© Simon Barrow is director of Ekklesia. His new book, Against the Religion of Power: Telling a Different Christian Story, is due for publication in 2024. His columns can be found here (and archived ones here). Twitter: @simonbarrow